FastDEA

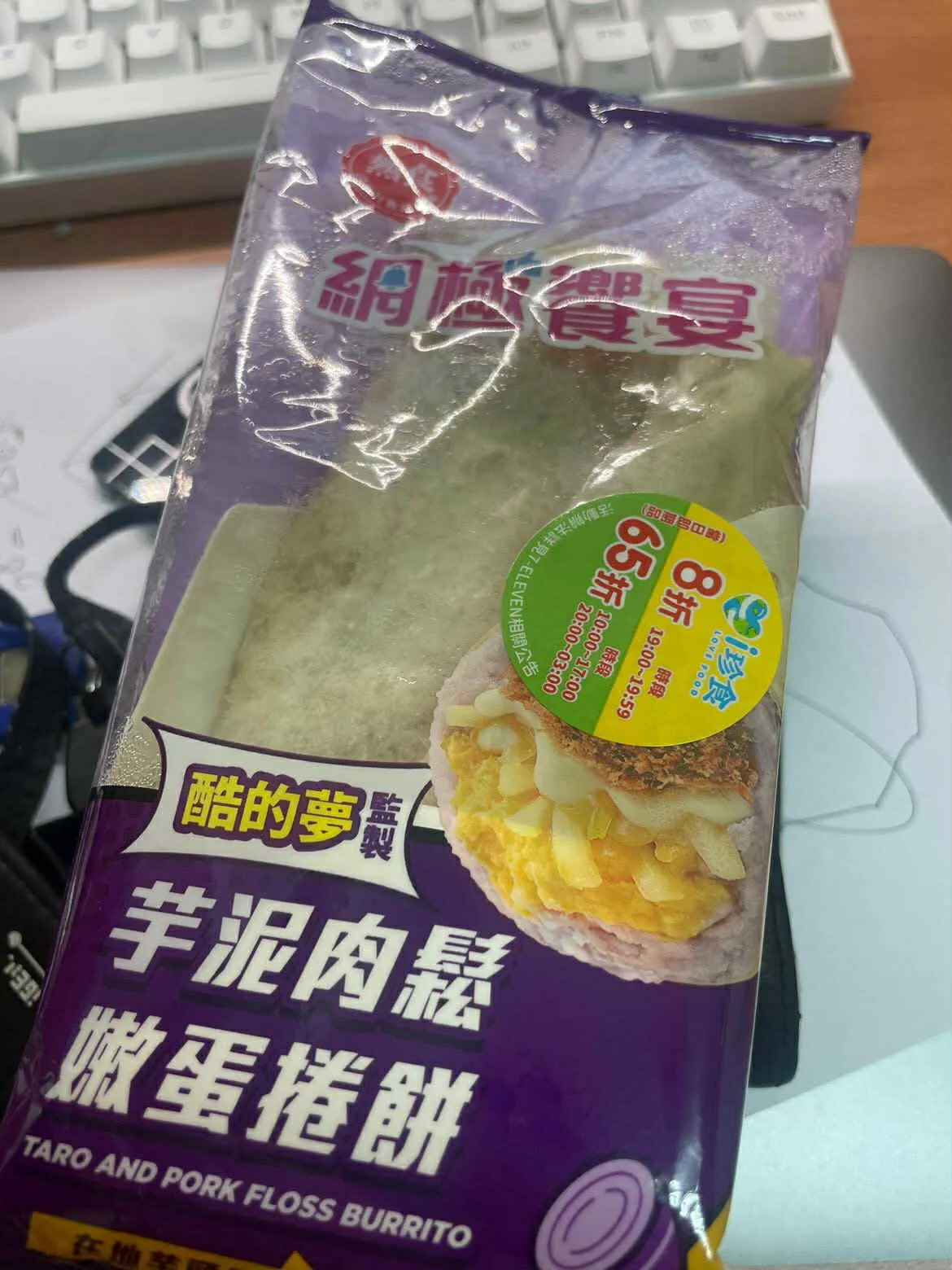

Last semester, I lived with 2 friends in a house near the Hsinchu Zoo. I’m a night owl, and one of my roommates is too. He and I often went to 7-Eleven around midnight to take advantage of the “i 珍食” discounts after 8 PM. During our walks to and from the convenience store, we would talk about everything.

i 珍食

i 珍食

One day, he mentioned that he hadn’t needed to go to the lab recently. This surprised me because I had always known him as a wet lab researcher. He explained that he was also working on some dry lab stuff at the time. When I asked what specifically he was doing, he said he was mainly using an R library called edgeR.

Being the 槓精 (naysayer) I am, I immediately responded, “R is trash. Use Python instead.”

My friend fired back, saying that if I wrote a Python version, he’d use it – otherwise, don’t even think about it.

This challenge prompted me to examine the topic more closely. That’s when I learned it was about differential expression analysis (DEA). But first, I needed to understand: why do we even need this?

DEA has several practical applications. For example, if you’re developing a new drug and want to identify which genes are upregulated (expressed at higher levels) and which are downregulated (expressed at lower levels), DEA can help. Additionally, scientists studying new diseases can compare gene expression between patients and healthy individuals to identify differences.

Now that we understand the uses of DEA, let’s explore how it is implemented.

A standard method is RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). According to the central dogma of molecular biology, DNA replicates to produce more DNA, is transcribed into RNA, and then translated into protein. Therefore, if you find that the mRNA level of a gene is very high, it’s likely that the protein is also highly expressed.

The modern RNA-seq process works as follows: We fragment the RNA and then reverse-transcribe it into complementary DNA (cDNA). Then we use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to obtain reads from the cDNA fragments. (A “read” is the sequencing output of a cDNA fragment.)

TODO

Once we get the read data, everything becomes dry lab work. First, the data is converted to FASTQ format, which contains both the nucleotide sequence and quality scores. These quality scores represent how reliable each base call is. Next, we align this FASTQ data against a reference genome (usually in FASTA format). The reference genome contains the complete sequences of all chromosomes. Based on this alignment, we obtain a SAM/BAM file that indicates which chromosome each read maps to and its position on that chromosome. By the way, the primary difference between SAM and BAM files is that BAM files utilize compression techniques and store data in a binary format, resulting in files that are significantly smaller than SAM files.

# FASTQ format

@SEQ_ID

GATTTGGGGTTCAAAGCAGTATCGATCAAATAGTAAATCCATTTGTTCAACTCACAGTTT

+

!''*((((***+))%%%++)(%%%%).1***-+*''))**55CCF>>>>>>CCCCCCC65# FASTA format

>gi|5524211|gb|AAD44166.1| cytochrome b [Elephas maximus maximus]

LCLYTHIGRNIYYGSYLYSETWNTGIMLLLITMATAFMGYVLPWGQMSFWGATVITNLFSAIPYIGTNLV

EWIWGGFSVDKATLNRFFAFHFILPFTMVALAGVHLTFLHETGSNNPLGLTSDSDKIPFHPYYTIKDFLG

LLILILLLLLLALLSPDMLGDPDNHMPADPLNTPLHIKPEWYFLFAYAILRSVPNKLGGVLALFLSIVIL

GLMPFLHTSKHRSMMLRPLSQALFWTLTMDLLTLTWIGSQPVEYPYTIIGQMASILYFSIILAFLPIAGX

IENY# SAM file format

readID43GYAX15:7:1:1202:19894/1 256 contig43 613960 1 65M * 0 0 CCAGCGCGAACGAAATCCGCATGCGTCTGGTCGTTGCACGGAACGGCGGCGGTGTGATGCACGGC EDDEEDEE=EE?DE??DDDBADEBEFFFDBEFFEBCBC=?BEEEE@=:?::?7?:8-6?7?@??# AS:i:0 XS:i:0 XN:i:0 XM:i:0 XO:i:0 XG:i:0 NM:i:0 MD:Z:65 YT:Z:UUNext, we compare the SAM/BAM file with a GTF/GFF3 file. The GTF/GFF3 file contains information about which chromosome each gene is on and its position within that chromosome. This allows us to determine which gene each read belongs to. (In practice, if a read maps to multiple genes, we discard it.)

GTF/GFF3 locates the genes. SAM/BAM locates the reads.

The result of this process is a read count table – a 2D matrix where each row represents a gene and each column represents a sample (one experiment or measurement). The values in this matrix represent read counts, which are the number of reads mapped to each gene in each sample.

# An example read count table

gene_id untreated1 untreated2 untreated3 untreated4 treated1 treated2 treated3

FBgn0000003 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

FBgn0000008 92 161 76 70 140 88 70

FBgn0000014 5 1 0 0 4 0 0

FBgn0000015 0 2 1 2 1 0 0So, we can finally get to the main point: what does edgerR do? Or what does DESeq/DESeq2 do? (DESeq2 is another popular tool in bioinformatics with similar functionality to edgeR.)

Their input is the read count table, and their output tells us which genes are upregulated or downregulated under different conditions. To do this, we divide our samples into groups – most commonly 2 groups – and compare them. But how do we quantify “upregulated” or “downregulated”?

To simplify, let’s focus on the two-group comparison case for now. (In the future, I may explore how to handle multiple groups or continuous conditions.In fact, you can also handle multiple groups by doing pairwise comparisons – )

Two values matter here: p-value and log2 fold change (log2fc). The p-value indicates the reliability of the result, and the log2fc value indicates the magnitude of upregulation or downregulation (expressed on a log2 scale).

There’s a famous visualization called a volcano plot. The y-axis represents – the higher the value, the more statistically significant the result. The x-axis represents log2fc, where positive values indicate upregulation and negative values represent downregulation. We typically set thresholds for both and log2fc (for both positive and negative values), and highlight all genes that exceed these thresholds. This makes it easy to visually identify which genes are significantly upregulated or downregulated.

You might wonder why we make things so complicated with p-values, log2fc, and so on. Why not simply sum or average the read counts for one group and compare them to those of the other group? The main challenge is that most experiments don’t have many replicates – three replicates are typical. However, we are all aware that experiments have measurement errors. Given the limited data available, a more sophisticated statistical model is necessary.

A traditional linear model is expressed as

where follows some probability distribution. In our case, represents the read count, is the baseline expression level (the intercept, representing expression in the control group), represents the condition (or more precisely, the design matrix – indicating whether a sample belongs to the control or treatment group), and represents the magnitude of differential expression.

However, this model has problems. First, it allows for negative values. For instance, if and your control group expression is very low, you might predict that the treatment group has a negative read count, which is meaningless. Second, the naive model assumes constant variance regardless of the expression level. However, based on experimental observations, highly expressed genes tend to have higher variance – a phenomenon known as the mean-variance relationship in count data.

This is why we use a generalized linear model (GLM). A GLM consists of 3 components: the exponential family distribution, the linear predictor, and the link function. The details of the exponential family are a bit beyond what I want to cover here, so just think of it as contributing to the probability distribution component. The linear predictor is similar to our original linear model (). Most importantly, the link function connects the probability distribution to the linear predictor.

There are several choices for the link function. In our case, we use the log link: . This ensures that no matter what equals, the mean () will always be positive (since ).

For the control group ():

For the treatment group ():

Taking the difference:

This is the natural log fold change. To convert to log2fc (which is more interpretable – each unit represents a doubling or halving):

We also use the negative binomial distribution because RNA-seq data typically exhibits overdispersion – variance much larger than the mean, which the negative binomial can model but the simpler Poisson distribution cannot. (For more details, I highly recommend this article: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/65361113)

The main pipeline of my implementation (FastDEA) can be summarized in 4 steps: normalization, dispersion estimation, negative binomial GLM fitting, and Wald test with plotting.

Normalization is necessary to account for differences in sequencing depth across samples. Sequencing depth refers to the total number of reads obtained for each sample. Some samples may have been sequenced more deeply than others, resulting in higher overall read counts even if the actual biological expression levels are the same. Without normalization, a gene might appear highly expressed simply because that sample had more total reads, not because it’s genuinely upregulated.

DESeq2 uses the median-of-ratios method for normalization. Here’s how it works: First, we calculate the geometric mean of each gene across all samples (multiply all values together, then take the nth root, where n is the number of samples). Then, for each sample, we divide the read count for each gene by that gene’s geometric mean, creating a ratio. We calculate the median of these ratios for each sample and refer to this as the size factor. Finally, the normalized read count is calculated by dividing the original read count by the size factor.

Although there are more sophisticated normalization methods that account for additional biological factors affecting sequencing depth (such as gene length and GC content bias), for proof-of-concept and simplicity, my FastDEA implementation currently uses the same median-of-ratios method. In practice,I work in log-space when calculating geometric mean, so I can use summation instead of multiplication, which avoids numerical overflow/underflow issues. I also filter out genes where all samples have zero read counts, as these provide no information for differential expression.

With normalization complete, we move to dispersion estimation. The negative binomial distribution has an additional parameter called dispersion (compared to the Poisson distribution). However, the fitting step cannot estimate dispersion and regression coefficients (beta values) simultaneously, so we must estimate dispersion first.

This step is where different implementations differ most significantly. You can employ various techniques, such as empirical Bayes and shrinkage methods, to estimate dispersion, which may enhance the final results. Again, for proof of concept and simplicity, I use a method-of-moments estimator combined with simple shrinkage.

Let’s examine it in detail. For the negative binomial distribution, the variance-mean relationship is:

where is the mean, and is the dispersion parameter. Rearranging gives:

Since we’ve normalized the data using size factors, we need to account for this in our variance calculation. The adjusted formula becomes:

(Note: here refers to the sample mean – the average normalized read count for that gene across samples.)

Why the size factor adjustment? The normalization divides counts by size factors, which affects the variance. The mean_of_inverse_size_factors term corrects for this scaling effect in the variance estimation.

However, raw dispersion (disp_raw) can be unreliable, especially for genes with low read counts (small sample sizes). So I apply shrinkage: I calculate the median of all raw dispersions across genes, then shrink each gene’s dispersion estimate toward this median based on a weight:

This weight depends on the sample mean read count for each gene. If a gene has high mean expression, we trust its raw dispersion more (weight → 1). If the expression is low, we rely more on the median dispersion (weight → 0). The final shrunken dispersion is:

You can think of this as:

In practice, I also filter out genes where:

- sample mean < 0.1 (too low expression to be reliable)

- disp_raw < 0

- disp_raw is infinite

The next step is fitting a negative binomial GLM, which yields the regression coefficients (beta values). Mathematical derivation shows this can be solved using Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares (IRLS). In fact, for this particular problem, IRLS is mathematically equivalent to the Newton-Raphson method.

If you’re unfamiliar with Newton-Raphson, it’s a classic method from high school math for finding roots of polynomial equations: you guess a value, calculate where the tangent line at that point intersects y=0 to get a new guess, and repeat until convergence. When we study calculus in college, we learn that the Newton-Raphson method essentially uses a Taylor expansion with the first derivative (slope) and second derivative (Hessian matrix) to approximate the solution.

As a computer science student, this raised a question for me: why not use the method commonly used in neural network training – gradient descent with only first-order derivatives (backpropagation)? Why use the Hessian matrix?

The answer: speed. By using second-order derivative information, we achieve much faster convergence. So why don’t we do this in deep learning? The Hessian matrix is extremely expensive or impossible to compute for large neural networks. However, in the context of fitting the negative binomial GLM, we can obtain this information relatively easily. Through mathematical derivation (the details of which are quite involved – I haven’t fully grasped them yet), we can show that this is equivalent to the IRLS process I’ll describe below.

To be continued…